June 30, 2020

Two Black Writers Help Me Make Meaning

A Perspective by Shanita Akintonde

This is the first of what we hope will be a continuing series, putting the spotlight on the Black Lives Matter movement and black writers. We want to hear your voice. Share your stories with us. Because your words matter. Send us an email if you'd like to contribute.

Black writers have long held the standard for their ability to serve as prognostic and compelling literary voices around issues of race, class, and identity. Their unique mastery of American letters helps make our nation’s current moral and political problems more palatable. This type of activism moves beyond books and serves as stellar examples of the power of prose.

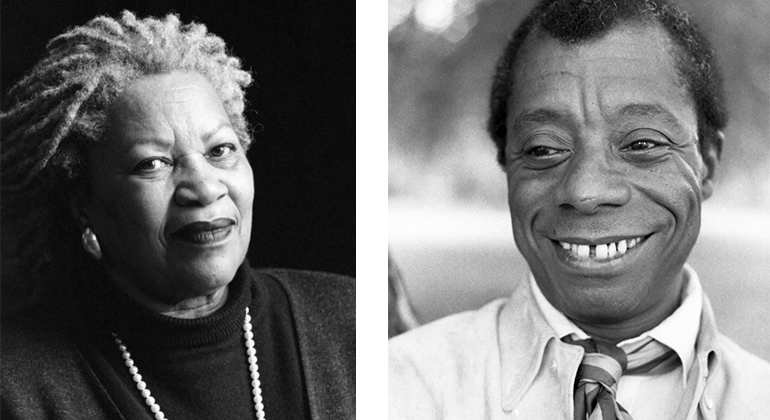

James Baldwin’s bold acclamation, “I am Not Your Negro,” was a prophetic prologue to, “I Can’t Breathe.” His timeless classic, The Fire Next Time (1963), was a conscious assessment of the racial divide that foresaw the need to “end the racial nightmare….and change the history of the world.” The national outrage that has erupted over the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor may offer the opportunity for our nation to heed Baldwin’s call.

Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison authored seven novels including Love, Jazz, Beloved, Song of Solomon, Sula, and The Bluest Eye. She was a lethal liturgy of patience and provocation whose nuanced retorts to repeated queries about “Why do you choose to write about Black people solely?” were met with such eloquent disdain that even sacrilegious savants shuddered.

Four years preceding the deaths of Floyd, Arbery, and Taylor, Morrison published an essay in the New Yorker about President Trump’s election. In her 2016 piece, she wrote, “So scary are the consequences of a collapse of white privilege that many Americans have flocked to a political platform that supports and translates violence against the defenseless as strength. These people are not so much angry as terrified, with the kind of terror that makes knees tremble.”

The irony that Morrison’s analogous wording to describe white fear that involved the same body part that a white officer used to kill George Floyd, an unarmed and handcuffed Black man, is not lost on me.

As protection for Black lives appears to become more and more malleable every day, writers, particularly Black writers, need to remain what Morrison calls “intellectually weapon-ized.”

To do so, I find myself turning to the works of Baldwin and Morrison. Written words, particularly during times of disruption, provide equal parts comfort, and convalescence. Baldwin exposes. Morrison dares. With blazing passion and prodding prose, their words offer succinct salvation.

Both writers revealed the need to pay attention to #BlackLivesMatter long before hashtag heretics. Slavery brought with it the need to rank color as an American definer. However, the superiority established by whites because of this rule is quickly dissipating.

Morrison called this dynamic the “fear of losing white privilege.” This kind of panic lead to the willful blockage of a Black jogger by three white men, and being gunned down in the street. It is the type of augmented anxiety that caused uniformed officers to kill two innocent, unarmed Black people, one of whom was a woman, shot to death inside her own home. As Morrison points out in another essay, this one entitled, Making America Great Again (November 14, 2016), a number of white Americans are “training their guns on the unarmed, the innocent, the scared, on subjects who are running away, exposing their unthreatening backs to bullets." Morrison continues, "The sad plight of grown white men crouching beneath their (better) selves…These sacrifices, made by supposedly tough white men who are prepared to abandon their humanity out of fear of black men and women, suggest the true horror of lost status.”

As writers, we have an opportunity to reinforce the prevalent mindset of respectful and mature people, ones who disdain the effort to retain superiority to others—especially Black people. Now is the time for writers, regardless of HUE, to write about those who need to have their respectful, law-abiding lives amplified. Failure to do so, based on Baldwin, would be a fait accompli.

The author stated…”it is ultimately fatal to create too many victims. The victor can do nothing with these victims, for they do not belong to him…They belong to the people he is fighting. The people know this, and as inexorably as the roll call — the honor roll — of victims expands, so does their will become inexorable: they resolve that these dead, their brethren, shall not have died in vain.”

Now. more than ever, I plan to channel Baldwin and Morrison, my writing standard-bearer and personal sister soldier, respectively. I will continue to do my part to change the narrative about the Black experience, from one begot with violence and victimization to one of excellence and distinction. Literature can serve as that equalizer. It is expansive, healing.

Stories serve as the basis for sharing the fundamentals of the human experience. I, for one, plan to push my pen to abate the moves of fearful derelicts and replace them with narrative that serves as a lens to unveil the nuanced layers of society and all its beautiful beings.

Shanita Baraka Akintonde, MBA, M.Ed. DTM is "a communication firecracker propelled by love." She has been writing since she first learned to spell her bologna's first name and has not looked back since.Today, you would be hard-pressed to find this 21-year academician, podcast host, newspaper columnist, and blogger, without a book, either one of the three she has co-authored, or one written by someone else. She is President of View Masters, Toastmasters Club, and Top Ladies of Distinction, Lincoln Park Chicago Chapter. Further involvement includes board positions at The Metropolitan, The National Speakers Association, and The American Marketing Association. Shanita is also the Immediate Past National Chair of the Public Relations Society of America’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee. In her spare time, Shanita is all about family. Whether spending time with her college sweetheart husband, Jimmy, or their two young adult sons, she is in her happiest place. The bologna sandwiches have been upgraded to steak and lobster. https://www.linkedin.com/in/shanitaakintonde/

Affiliates/Partners

Testimonials

Contact

Join CWA

Member Directory

My Account

Writers Conference

Presenters

Agents and Publishers

Pitch Sessions

Sponsors

Scholarships

Speaker Registration

Book of the Year

Spirit Award

First Chapter Contest

Resources

Home

Chicago Writers Association

info@chicagowrites.org

Make a Difference!